How Gilded Age Society Accidentally Wound Up on Fifth Avenue

The march uptown, featuring NYC historian Keith Taillon.

Hello, and welcome to the ~first~ issue of Second Story, a weekly newsletter for old house enthusiasts and history fanatics! If you never want to miss out, please make sure to subscribe.

Walk around Manhattan, and you’ll notice pockets of beautifully grand houses all over the city, from the Greek revival homes on Washington Square Park and Gramercy to the mansions on E79th and 5th. Sometimes in seemingly random locations (Murray Hill? Really?) these houses are not only fun to look at, but they also indicate how this city developed—and what drove neighborhoods to fall in and out of fashion.

“The wealthy hopscotched their way up Manhattan,” Keith Taillon, New York City historian (@KeithYorkCity on IG) and author of Walking New York: Manhattan History on Foot (coming out April 15th) explained one cold Tuesday morning over coffee. “In the 19th century, a pattern of movement formed. The wealthy crept further and further uptown to get away from the commercial center of a dirty, dense, and growing city—but the city would always catch up, and they would move again.”

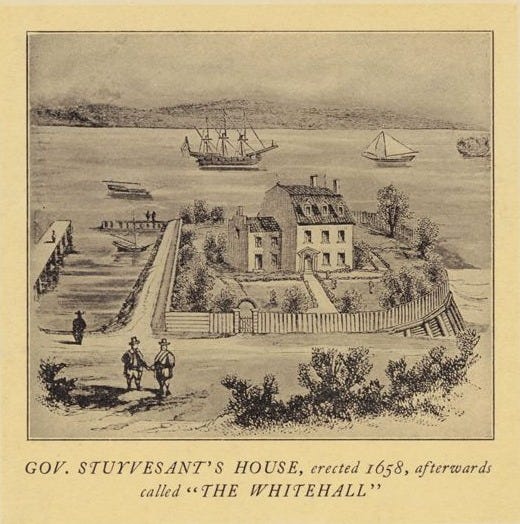

When New York City was founded in the 1620s in what’s now the Financial District, though, the mindset around where to live was entirely different. The Dutch colonists prized the convenience of living near the heart of the town—then a walled fortress—by the waterfront and their businesses on bustling Pearl Street. “The most impressive house was Whitehall, Peter Stuyvesant’s big whitewashed Dutch style manor house right on the water,” Taillon said. “Right behind where the Custom House is today.”

As the city expanded and wealthier British colonists arrived in the 18th century, New York’s population grew, and the emphasis shifted toward living around parks. Broadway became a dividing line: the Dutch stayed east of Broadway, and the British, not wanting to live in the older Dutch homes, stayed west.

“There wasn’t really an impoverished class yet,” said Taillon. “There were laborers, and there were wealthy people, but it was very much the norm that everybody had a house. That changed with a post-revolutionary influx of people from other cities, the countryside, and other countries, especially Europe, who settled in the older, denser areas east of Broadway.”

A few decades later, the Erie Canal opened. New York’s population skyrocketed, and New York Harbor became an epicenter of American commerce. Current day FiDi became crowded, dirty, and disease-ridden, and the wealthy didn’t want to live near that. So, Taillon explained, they looked northward.

“Wherever they went trying to get away from the urban center, businesses followed to be close to their customer base. Naturally, industry followed to produce the goods to sell, and the working class would move nearby. Then, the cycle would begin again.”

With Broadway as the elite street guiding where to go, society moved from Bowling Green to east Broadway to Chambers street and current day Soho and Tribeca. Once those areas began to decline due to this cycle, Taillon explained, people moved north of Houston Street to Washington Square Park and Astor Place area, which both rose to prominence in the 1830s. Tompkins Square Park was also developed around that time—but turns out, the wealthy didn’t want to live that far east of Broadway.

“There was an excitement and a newness to New York,” Taillon added, noting that the city was only about 150 years old at this point. “That excitement allowed the wealthy to untether themselves from location in a way their European counterparts with ancestral manor homes couldn’t do.”

Meanwhile, some of the oldest Dutch and British families were clinging onto their downtown homes. Caroline Schermerhorn—later Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, Mrs. Astor—was born in 1830 on Battery Park, long after the center of gravity moved. Her parents eventually moved the family uptown to Bond Street.

By the 1850s, society had reached Madison Square Park, which crosses with Fifth Avenue. To the east, a train ran down Fourth Ave (current Park Ave), and the well-to-do didn’t want to live around the smoke and the noise. The blocks to the east were better suited to the hospitals and horse stables that filled them. To the west was an entertainment district with theaters, hotels, and gambling halls.

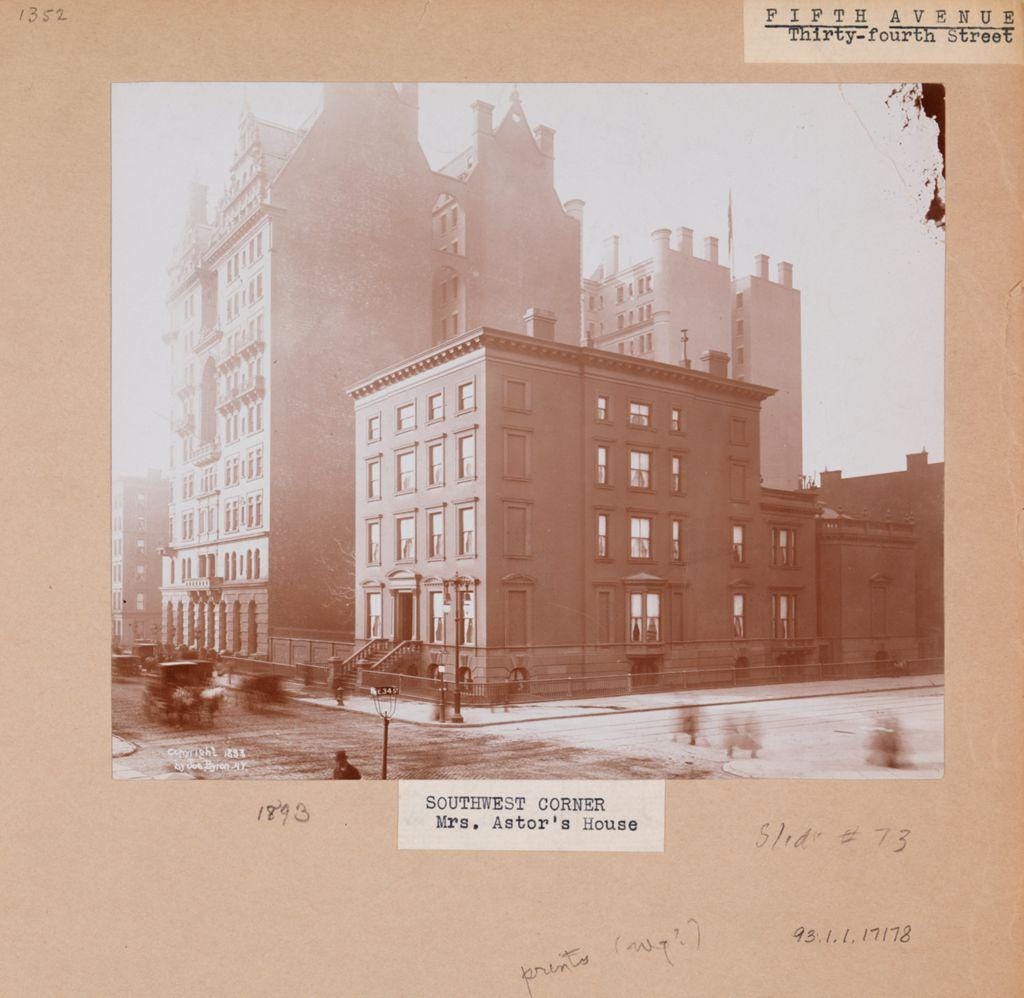

“The narrow strip of Fifth and Madison Avenues into the East 30s, away from the commotion, rose almost accidentally as the new center of elite living.” And so, Murray Hill was it, with the Morgans building their mansion (and library!) on E36th, and the infamous Astors just a few blocks away on East 34th Street.

Murray Hill had staying power, due in large part to Queen Bee Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, who centralized the boundaries of society around her mansion on 34th Street and Fifth Avenue, where the Empire State Building stands today. Taillon explained that nobody really anointed Mrs. Astor, but rather wealthy New Yorkers had a hunger for a social structure that, up until this point, hadn’t really existed. People were quick to follow Mrs. Astor’s lineage-based organization of society.

“It became a gilded competition of who had the most Stuyvesant or Van Rensselaer or Livingston blood in them.”

By the Industrial Age, post-Civil War, there was a new class of wealthy New Yorkers. These tycoons may not have had fancy blood, but they did have lots of money—and a desire to build fabulous houses to match their wealth. Side Note: Season 3 of The Gilded Age, when?!

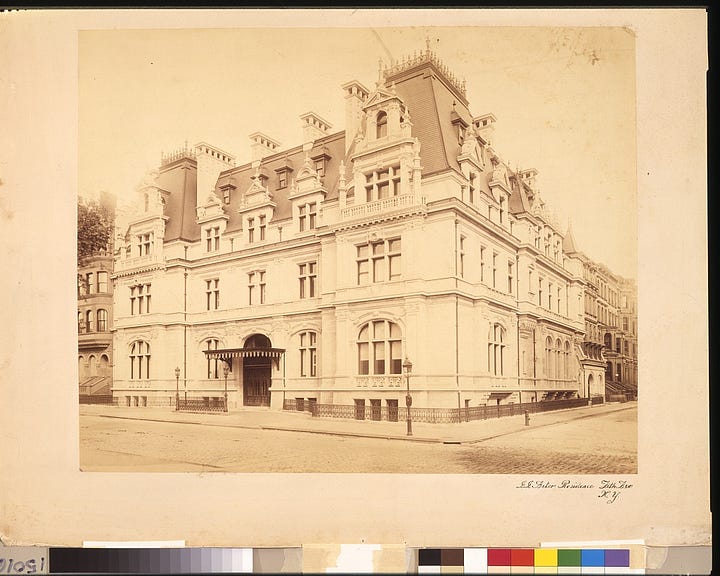

The only problem? There was no space to build in Murray Hill, which had become filled with old fashioned brownstone mansions packed as close to the Astor house as possible. The children of Cornelius Vanderbilt were the ones to defy Mrs.Astor’s strict boundaries by going north of 42nd Street, a former no-man’s land, to build “Vanderbilt Row” on the empty 5th Avenue lots in the 50s following the Commodore’s death in 1877.

“That began the decline of Murray Hill as the neighborhood of choice,” Taillon said. “When Caroline finally decamped in 1894, instead of joining the Vanderbilts, she leaped right over them and built her mansion on Fifth and E65th, and she did for the Upper East Side what she had done for Murray Hill a generation before.”

In 1901, Andrew Carnegie built his imposing mansion—now The Cooper Hewitt—on E91st and Fifth, and soon the blocks between E79th and E96th were filled with townhouses and mansions. While it’s no secret that the Upper East Side continues to be home to some of the most exclusive and expensive real estate in the city, the expectation at the time was that the march northward would continue.

“There was a newspaper article that projected the movement of the center of society up the island through the year 2000,” Taillon said. “They expected the center to eventually be around W168th street!”

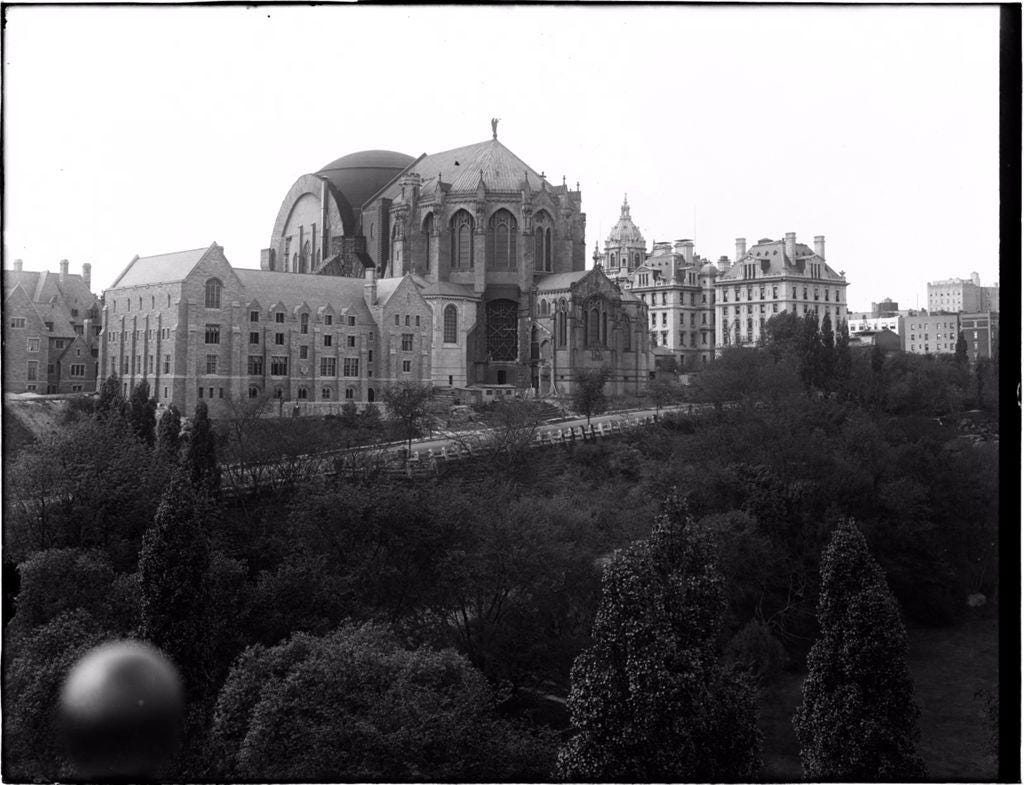

And developers built on that expectation, perhaps most visibly with St. John the Divine Cathedral in Morningside Heights. “That's also why Morningside Heights was treated as what the press called the acropolis of the New World,” Taillon added. “The idea was, we'll build a new center for the city up there so that by the time the city catches up to it, we've got a a city center that we can be proud of.”

The city hit a sort of development stasis in 1916, when New York passed the country’s first comprehensive zoning package that separated residential, commercial, and industrial for the first time, effectively stopping the uptown cycle of industry following commerce and residential in its tracks. The zoning law was just one of a series of factors, compounded by the fall of the Gilded Age, two world wars, and the Great Depression, that fundamentally altered the way New Yorkers moved about the city.

“In the first decades of the 20th century, you actually start to see people moving back downtown, to places where their grandparents might have lived,” said Taillon. “That’s in part why you see interesting renovations of townhouses in the village and Gramercy Park around that time.”

Chasing the “next” neighborhood might be a centuries old game, but it’s one that every city dweller is familiar with. Just a few years ago, the New York Times reported how Brooklyn Heights has become the darling neighborhood of celebrities (for good reason…those homes are incredible, some with sweeping harbor views). And any New Yorker can tell you that daydreaming about real estate—a new neighborhood, a new apartment—is the one thing we all have in common. Perhaps we’re not as different from 19th century New Yorkers as we might think: “It’s in that early willingness to move—to try something new, establish a whole new neighborhood,” Taillon said, “Where you find the core of what New York City is to the present day.”

Great article! One thing I would note is how John Jacob invested his pelt trading earnings into Manhattan real estate, where he made a second fortune anticipating the northward advance of the development of the Broadway corridor.

So interesting!! Thank you!