Welcome to Second Story, a newsletter for people who love old houses and secretive rituals. Not on the list? Subscribe below! If you like what you read, please tap the heart at the bottom of the page to boost this post in the Substack algorithm. Thank you! - Robert

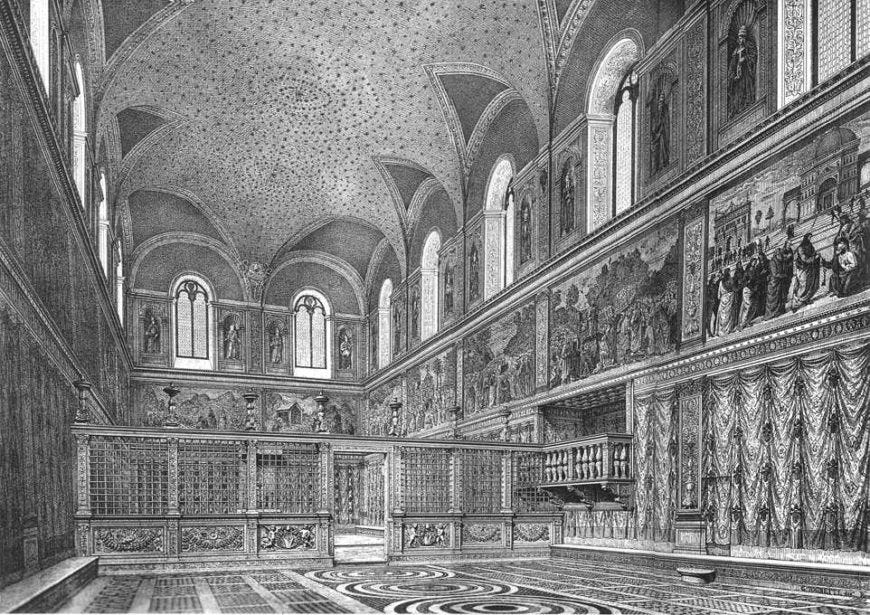

Few rival the Catholic church in the art of pageantry—and that’s never more apparent than during the conclave, when cardinals are sealed within the Sistine Chapel under an oath of secrecy as they mysteriously elect the next pope. Leaks result in excommunication. Success (or continued duty) is only signaled by the colored smoke as the 133 cardinals burn their ballots inside one of the most significant and beautiful rooms in the history of Western art.

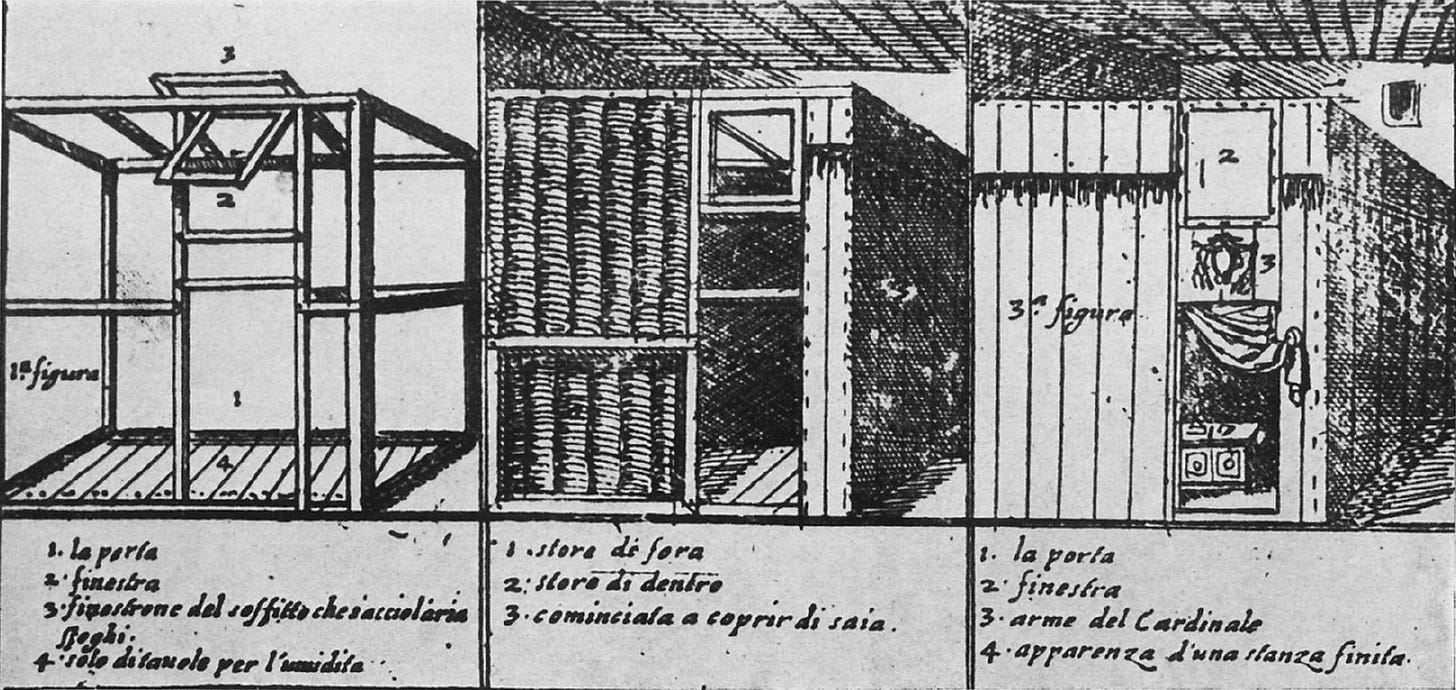

But the Sistine Chapel initially played a very different role in the conclave. Built under Pope Sixtus IV in 1481 on the foundation of a medieval chapel, the Sistine Chapel first served as a dormitory for the cardinals from when it was consecrated in 1483 through the early-mid 16th century. Although there were some exceptions—it first played host to the 1492 conclave—the Sistine Chapel was most often transformed into a sort of bunkhouse, with wooden cells constructed inside.1

When preparations were complete, the Sistine Chapel resembled a hospital ward: beneath the painted walls stretched two rows of wooden-framed cubicles divided by a narrow passage (only interrupted near the centre by the screen or cancellata); each cell was covered in coloured cloth-by convention cardinals created by the deceased pope had violet colour, the rest had green-and each bore an individual number or letter and probably the occupant's coat of arms.2

At that time, the Sistine Chapel didn’t have much of the artwork it’s famous for today. Michelangelo’s iconic ceiling3 wasn’t painted until 1508-1512, and his Last Judgment wouldn’t be completed until 1541. Instead, a deep blue ceiling dotted with golden stars watched over the sleeping cardinals alongside frescoes by Renaissance masters like Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino—scenes from the lives of Moses and Jesus lining the walls.

The cubicles were assigned by lottery, and it didn’t take long for the cardinals to ascribe divine, almost superstitious, meaning to their assignments, believing their placements could mystically indicate the next Pope:

The more persistent belief seems to have been that the cardinal to become pope would obtain the cell beneath Perugino's painting of Christ giving the keys to St. Peter…But a sporting chance was also held for the cardinal in the furthest cell from the altar beneath the opposite wall, under the detail in Signorelli's Last Acts of Moses, showing Moses handing on the golden rod to Joshua. There was also hope for the cardinal placed nearest to the point in the chapel where the papal throne normally stood.4

Sometimes, the omens were accurate: In 1503, Cardinal Piccolomini drew the coveted cubicle beneath Christ giving the keys to St. Peter, and he was later elected Pope. Other times—like in 1521 when an absent cardinal became pope—the theory did not prove true.5 Of course, this was a somewhat self-fulfilling prophecy, as the cardinals believing in the omens were also the ones voting and thus able to realize their superstitions. This phenomenon, though, reveals how even its early days, cardinals viewed the Sistine Chapel as a uniquely sacred space, where these relatively new frescoes could channel divine intention. While the Sistine Chapel eventually lost its role as the dormitory due to capacity issues, it’s no surprise that the chapel would eventually become the permanent home of the conclave.

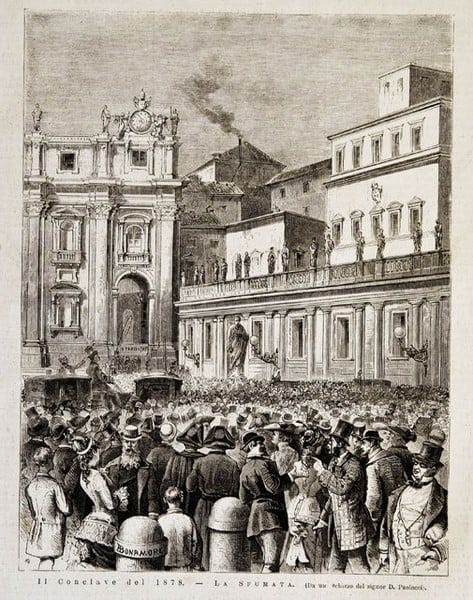

That didn’t happen until 1878, though. The exact reasoning is unclear—I couldn’t find any archival announcements or 19th-century reports—but it does make sense. The Sistine Chapel was built to host major papal services, and its thick brick walls and fortress-like exterior indicate it’s just as much a stronghold as it is a sanctuary. It’s a secure and controllable location.

While famously doors are sealed and windows are boarded up—conclave comes from the Latin cum clave "with a key,” to reference locked doors—in recent years measures have been taken to bar any electronic interference that include a temporary floor with tiles to block cell phone activity and scramble any spyware.

There is, of course, one way that the cardinals can communicate with the outside world: Smoke signal. I can truly only imagine the safety protocols required to install a stove in one of the most important rooms in the world6, but there are technically two stoves, one from 1939 and the other from 2005, that make a temporary home in the Sistine Chapel. The letters are burned in the older stove, which triggers the smoke-producing device in the newer stove.

While the use of smoke dates back a few centuries, the clear distinction between black and white smoke is a relatively new addition to the conclave’s nearly 800-year-old ritual. Georgetown University claims the first use of white and black smoke was in 1914, but newspapers published during that conclave tell a different story. At that time, it seems that the presence of any smoke indicated the voting was unsuccessful. Ballots would be burned with straw to conjure the smoke signal to the crowds. The first time I found clear reference to white and black smoke was in The New York Times during the 1958 conclave.

While straw was previously used, now the smoke is chemically produced by cartridges designed to emit either black or white smoke for about seven minutes. Not even rituals as old as the conclave are safe from modernization and optimization for video!

As I write this newsletter, though, white smoke just went up. A new (American!) pope has been elected, and with that, another conclave comes to an end. Though often seen as a timeless ritual, the conclave has nevertheless evolved over the centuries into the iconic process that it is today, and it will undoubtedly continue to evolve. So, if you ever find yourself in the Sistine Chapel, watch where you stand: it could be where a very lucky cardinal once slept—or where the stove stood to announce to the world that he has been elected pope.

D. S. Chambers, “Papal Conclaves and Prophetic Mystery in the Sistine Chapel,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 41 (1978): 323, https://www.jstor.org/stable/750878.

Ibid.

Fun fact: Apparently, Michelangelo resisted Pope Julius II’s commission. He considered himself a sculptor, not a painter, proving that even Michelangelo suffered from impostor syndrome, and you should feel empowered to go forth and do whatever it is that you’re dreaming of doing, even if you don’t see yourself that way right now.

Ibid.

Ibid., 326.

Especially after the fire at Notre Dame!

Fascinating - thank-you!

Yet again a topical & interesting read. Thanks.