666 Park Avenue: NYC’s most palatial, mysterious maisonette

The 27-room triplex, known as the most remarkable apartment of its kind, is hidden within the base of one of the city's notoriously exclusive co-ops.

Welcome to Second Story, a weekly newsletter for those who love old houses and mysterious maisonettes. Subscribe below if you’re not already on the list. This newsletter is entirely reader supported — and I’m offering the first month free for everyone!

The most legendary prewar apartments in New York City history have one thing in common: They no longer exist. From Condé Nast’s 30-room penthouse at 1040 Park Ave to Marjorie Merriweather Post’s legendary triplex, these mansions in the sky—along with so many others—were subdivided into smaller suites after the original tenant vacated.

One New York palace, though, has quietly survived: the stupendous 27-room triplex maisonette in the base of 660 Park Avenue, one of the Upper East Side’s searingly exclusive co-ops. The most remarkable apartment of its kind, it’s shrouded in secrecy, thanks to a scarcity of photos and one extraordinarily difficult to locate floorplan. Today, though, I’m shining a light on this mysterious maisonette, with a history almost as intriguing as its custom address: 666 Park Avenue.

What is a maisonette?

In short, a ground-floor apartment with a dedicated street entrance. A maisonette strikes a balance between apartment and townhouse living, offering the privacy of a separate entrance without sacrificing the convenience of building services and staff. Many maisonettes are one floor, but others in especially grand buildings—like 820 Fifth Avenue—are two floors. 666 Park Avenue, not to be outdone, is three, and uniquely has its own address separate from the main building.

The Main Building: 660 Park Avenue

At the corner of East 67th Street, 660 Park Avenue was completed in 1927 by York & Sawyer, the classical architecture firm behind other buildings like the New York Historical Society and the New York Athletic Club. The distinguished 14-story co-op does not allow financing1 and has just 12 residences, mostly full-floor 13-room apartments.

The building, with its strong cornice, serene facade, and boldly carved limestone base, draws inspiration from Renaissance palazzos. The maisonette’s grandeur is visually defined on the exterior, where the casement windows on upper floors are exchanged for monumental sashes that hint at the palatial entertaining rooms inside. The maisonette is contained within the limestone base, separated from the rest of the building by a belt course and balustrade.

The Maisonette: 666 Park Avenue

The maisonette entered society not unlike a debutante, with an announcement in The New York Times. “MRS. VANDERBILT’S HOME” the headline proclaimed one Sunday in March 1927, “New three-floor apartment at 660 Park Avenue ready soon.”

Virginia Fair Vanderbilt, freshly divorced from William K. Vanderbilt, Jr., had been living in the family’s Stanford White-designed mansion at 666 Fifth Avenue, when she decided it was time for a change as Fifth Avenue was becoming a commercial thoroughfare.

She sold 666 Fifth to a developer and planned to join other families of the 400 uptown. The Times reported that she bought the first three floors of 660 Park Avenue for $195,000 ($3.6M today) to build a custom spread, not unlike what Marjorie Merriweather Post did atop 1107 Fifth Avenue just two years prior. Like Marjorie—who demanded her triplex share an address with her mansion—Virginia appears to have orchestrated a similar move: although her apartment was within 660 Park Ave, the maisonette would carry a separate address, 666 Park Ave, to recall her former home on Fifth2.

“Each floor is 60 by 100 feet, permitting 13 rooms to a floor,” reported The Times as it gave the first hints of the space. “Mrs Vanderbilt, however, is not going for numerical superiority. In her apartment there are 27 rooms, some of them duplex in character.” How grounded of her.

But Virginia would never complete the apartment as planned. The following year, The Times announced that she sold the palatial (yet unfinished) apartment to the president of National Distillers, Seton Porter. “This is generally considered one of the finest apartments ever built in New York,” described The Times 97 years ago today, on April 25, 1928. Virginia would go on to land at a townhouse in the East 90s.

Seton Porter oversaw the installation of the vast rooms, sourcing paneling not from the offices of York & Sawyer but from European manors and castles to bestow generational history and importance to the new home.

There is unfortunately no publicly available floorplan—I tried contacting Columbia University which has the archives of York & Sawyer, the DOB, and the Office of Metropolitan History3—and the apartment has really only been photographed three times: Once when Seton Porter owned it, once when Leslie Samuels owned it, and once by Architectural Digest in March 2002. However, I did manage to find an adequate formal description of the apartment in New York’s Fabulous Luxury Apartments by Andrew Alpern from 1975.

“A flight of broad marble steps leads to a foyer whose walls are carved Caen stone. On this level is a double-height living room, a double-height dining room, and a double-height library, as well as a study, the kitchen, service pantries and the servants’ hall. The second level includes separate men’s and ladies’ coat rooms and six servants rooms. The third level contains the master suite (bedroom, sitting room, dressing room and bath) plus two other master bedrooms (each with its own bathroom) as well as a sewing room, extensive closet space, and five additional servants rooms.”

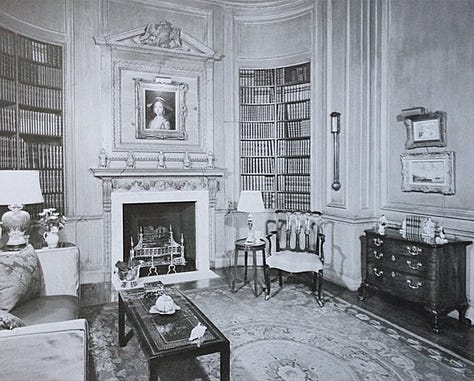

I would expect that the roughly 18,000 square foot apartment has more than just three principal bedrooms, especially if there are (at least) 11 staff rooms. Other descriptions of the apartment have noted that there is a charming card room off the library, “a reminder that this is an apartment laid out for a certain way of life.”

Undoubtedly the crown jewel of the apartment is 50-foot long, 24-foot high living room with elaborately carved early 18th-century pine paneling4 from Spettisbury House in Dorset. Spettisbury House was built in 1740 and demolished in 1927 after being used as a convent and school. Many of the rooms in the great house were sold off to Americans looking to imbue their homes with a sense of European gravitas. That included the magpie-like William Randolph Hearst, who reportedly first purchased the living room before selling it during bankruptcy.

The living room leads directly into an equally vast dining room, anchored by a fireplace and thick band of crown molding. Also on the principal floor is the library, finished in paneling sourced from a house in Grosvenor Square in London. Other rooms upstairs were sourced from Chateau de Courcelles in Sarthe, France.

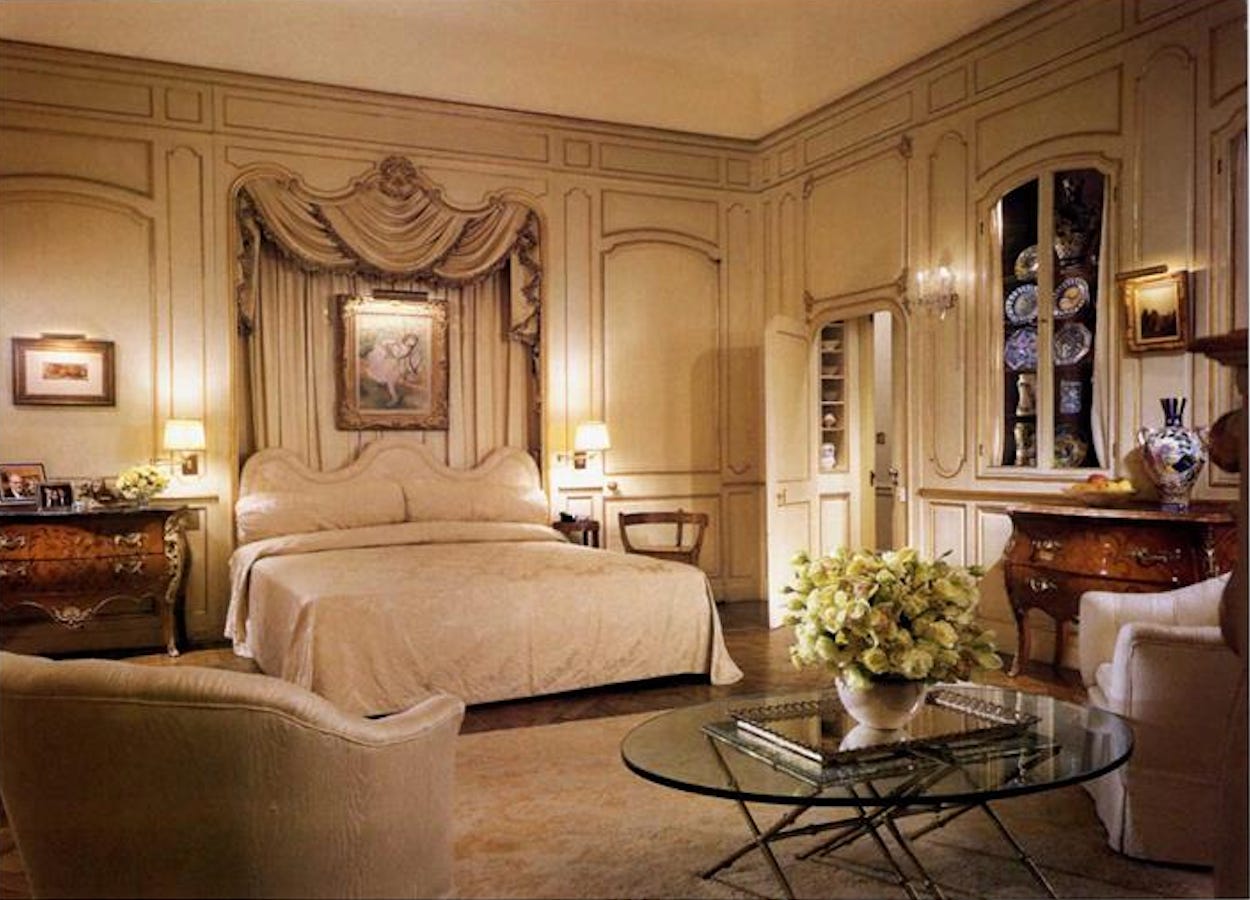

The most grandly scaled rooms are on the second floor and the more intimate “family quarters” on the third floor, as Architectural Digest described in a March 2002 feature.

While we can’t cross reference this description with a floorplan (rude), it is consistent with a description provided by philanthropist Leslie Samuels, who owned the apartment from 1952 to 1981 with his late wife, Fan Fox.

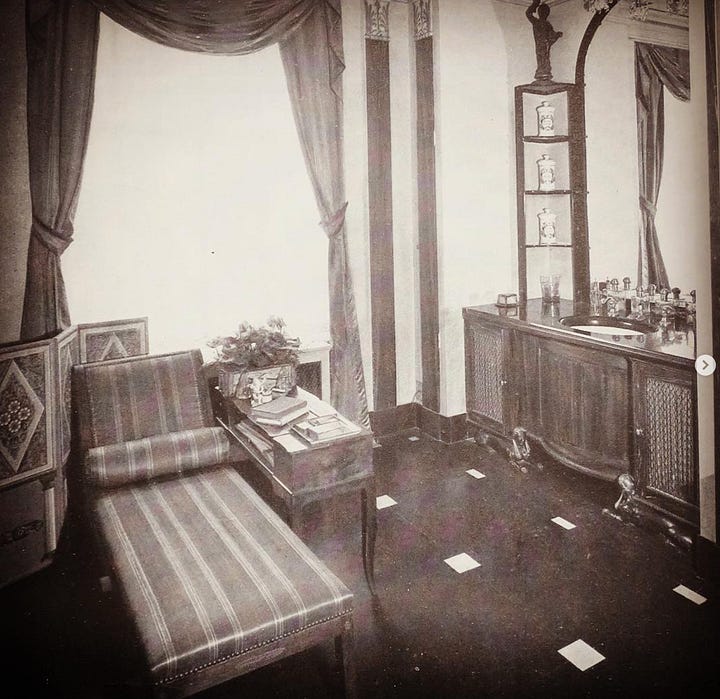

"Every night when my wife [Fan Fox Samuels] was alive, we'd dress for dinner,” Leslie Samuels, the fifth owner of the apartment, described to The Washington Post in 1981 when he listed the maisonette for $9M. “We'd have our drinks in the drawing room, and then, after dinner, we'd come up here [to a smaller sitting room]."

Samuels was referring to a room clad in Louis XIII paneling from the Chateau de Courcelles, which The Washington Post reported was complete with oak-beamed ceilings and a fireplace with original briques from Feucherolles and a parquet floor from the Chateau de la Muette. Another reclaimed room from France, used as a bedroom, featured painted chinoiserie paneling and a stone fireplace.

The maisonette has had six owners since it was completed nearly a century ago, and they have all shared a respect for the architecture and history of the fabulous apartment. Keep in mind: These interiors are by no means protected. They could easily have been ripped out sometime over the years, just as the interiors of Jackie Kennedy’s apartment were gutted upon its sale to David Koch in 1996. Not so at 666 Park, which did undergo some renovations in 1952 when Leslie Samuels purchased the maisonette, but the principal rooms with their period boiserie have survived untouched.

The maisonette represents a truly rarified way of life, one of bygone grandeur and formality. Whenever I bike by those oversized windows facing Park Avenue, that’s what I think about most: How does life unfold inside the maisonette? What does a 666 Park Avenue dinner party look like?

“The Samuels family often had 20 for dinner,” Maria Carle, one of their 12 members of staff to Leslie and Fan Fox Samuels recalled to The Washington Post. "For 20 people, [Mrs. Samuels would] have five waiters for the table. She liked to do everything right. She was very precise.”

Carle continued: “Every morning they'd have breakfast at 11:30. He'd eat down here, but Mrs. Samuels would have her upstairs…Then they'd read their mail and then go out window shopping in their car with the chauffeur, or perhaps to some exhibit. They liked to come back with some little pretty things for the house."

Leslie and Fan Fox were married for 41 years before she passed away in 1981. Leslie wasted little time before moving into a smaller apartment at the Waldorf. "I couldn’t stay here any longer after she died," Leslie Samuels said. "Everything here we bought together. We were always together.”

The maisonette last traded back then, when it was sold by New York real estate icon Edward Lee Cave for $9M ($31.6M today). It was bought by Arthur Sackler, who lived there until his death in 1987 with his wife, Dame Jillian Sackler, who reportedly still calls the maisonette home today.

She welcomed Architectural Digest into the maisonette 23 years ago, in March 2002. Writer Michael Frank centered the profile around how the Sackler art collection complemented the impressive architecture of the home.

“It’s been a great privilege to live here,” Dame Jillian said in the feature. “My relationship to the apartment… is only temporary.”

Over lunch recently, a friend described homeownership as a kind of stewardship—that we don’t own homes so much as we preserve them for the next generation. Dame Jillian’s words echo that philosophy, knowing she’s just one in a line of those entrusted with preserving this remarkable place. Whoever comes along next won’t just acquire a trophy apartment. They’ll assume the task of protecting one of the last prewar icons: the Maisonette at 666 Park Avenue.

Second Story is a reader-supported newsletter. If you like what you read, please consider becoming a paid subscriber so you don’t miss out on what’s next!

That means any purchase must be all cash, and the board will expect applicants to have multiples of the apartment’s value in post-closing funds.

This is kinda unconfirmed, but I would be shocked if this was untrue.

If anyone has leads on a floorplan, please! I am all ears.

Both The New York Times and Architectural Digest say that it’s 17th-century paneling, but everything I found dated Spettisbury House to the early 18th century.

Thank you for your work and detail on this.

These interiors are LUXE, wow!