Hearth & Home: A (brief) history of the fireplace—and how to actually cook in one!

Break out that Tuscan grill, featuring recipe developer and cookbook author Alexis deBoschnek.

Welcome to Second Story, a free newsletter for old house fanatics and history enthusiasts! New issues post every Friday, and if you like what you read, please subscribe.

Every Presidents’ Day weekend for the last eight years, my partner John and I have rented a beautiful Dutch stone farmhouse in Stone Ridge with close friends. Known as the Wynkoop House, it’s any old house fanatic’s dream, unique for its size, gambrel roof, and beautifully preserved paint and wood paneling. (You, too, can rent it here!)

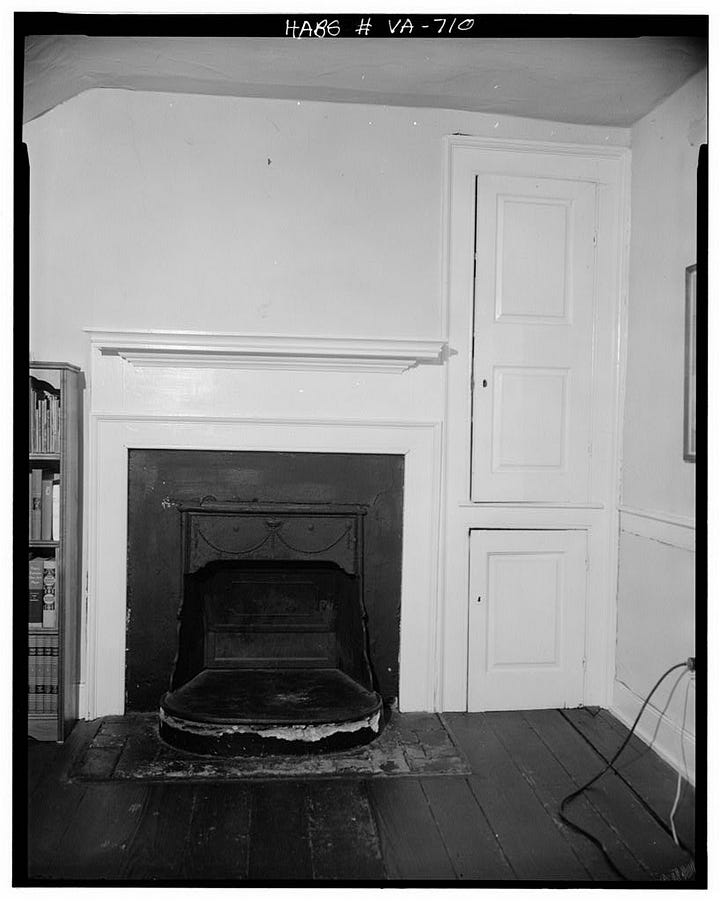

Oh, yes, and its fireplaces. This 18th-century house—which hosted George Washington one November night in 1782—has nearly one per room (the ideal ratio of fireplaces, IMHO) with an impossible-to-miss, mammoth cooking hearth in the kitchen, which likely dates to the late 17th century.

Apart from wide-plank floorboards, divided light windows with hand-blown wavy glass, and carved moldings, I believe that nothing evokes the romance of a historic home quite like a fireplace that can be put to good use on a cold night.

The earliest fireplaces in Europe were simply open hearths in the center of the room—not contained by a firebox or flue—and smoke would gather in the eaves and escape slowly out through the roof. In the 1300s, fireplaces began to appear in the wealthiest households, but their crude designs barely funneled smoke out of the building. By the 16th century, fireplaces had developed further and become more widely accessible, but their still inefficient designs meant they were drafty, smoky, and didn’t heat well. Anyone who has used a fireplace can tell you that most of the heat is lost up the flue, and the warmest spot is directly in front of the fire, where you’re more likely to be scorched than heated1.

Fireplace design didn’t really change that much by the time British colonizers started building early American houses stateside. Although the English knew of more efficient heating methods, like the stoves that continental Europeans had been using for generations, they were reluctant to give up the tradition of heating by hearth, and so fireplaces became the default in 18th-century colonial homes2.

Things began to shift in the mid-1700s, when Germans arrived in Pennsylvania, stoves in hand. In 1742, Benjamin Franklin riffed on the imported stoves by inventing what became known as the Franklin Stove, a small open cast-iron insert that used baffles, or channels, to heat and then expel air. The stoves could be retrofitted into any existing fireplace. By the Revolution, Franklin stoves had joined a growing trend of clever stove designs that could become quite ornate—a topic for another newsletter3.

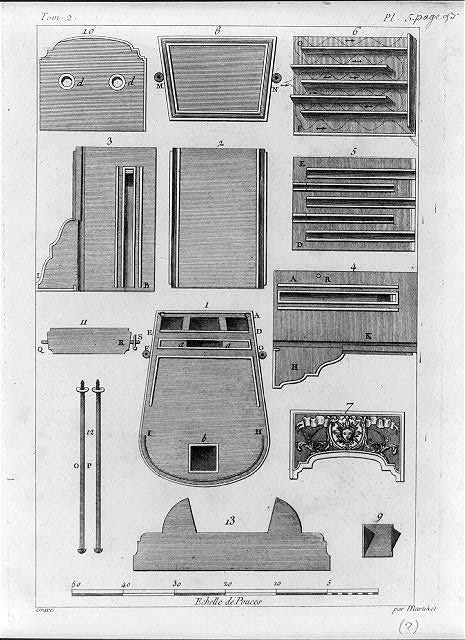

Shortly after the Revolution, another innovation changed the shape of fireboxes and chimneys on both sides of the Atlantic: the Rumford fireplace, which was named for its inventor, “Count Rumford,” an American-born loyalist (originally named Benjamin Thompson) who promptly moved to London in 1776 and later became a Count of the Holy Roman Empire. Thompson was highly interested in the science of heat and sought to redesign the fireplace to resolve the wildly inefficient and smoky flues that made London notorious4.

The result was distinctive and effective. “In the fireplaces I recommend,” Rumford wrote in his essay “Chimney Fireplaces,” “The back is only about one third of the width of the opening of the fireplace… and the two sides or covings of the fireplace, instead of being perpendicular to the back, are inclined to it at an angle of about 135 degrees.” These changes swiftly directed air into the firebox and up the chimney, thus burning wood cleanly. The splayed sides efficiently reflected heat into the room.

Also driving the popularity of Rumford’s innovation was its basis on proportion, meaning it could be scaled down to a bedroom fireplace or scaled up to my favorite—a cooking fireplace. After all, who doesn’t love the idea of a cozy hearth in the most used room in the house?

Contrary to living room or dining room fireplaces, which are often decorated with detailed mantels and tile surrounds, a cooking fireplace is defined by utilitarianism, with larger dimensions to accommodate the act of cooking. There is often an iron crane mounted to one side for hanging pots over the fire, and the mantle is generally plain and functional. If you’re lucky, there is also a beehive oven to the side5.

While today, whether used for heating or cooking, fireplaces are admittedly a little obsolete, that doesn’t mean your next great meal can’t come from one!

“Cooking in a fireplace is all about making sure you have a good fire going,” Cookbook author and recipe developer (and substacker!) Alexis deBoschnek told me one day when I was explaining how my one and only attempt at fireplace cooking—toasting bread in the Wynkoop kitchen fireplace—ended up in a inedible mess. “It sounds as though your fire wasn’t fully lit.”

Alexis, who I first met on Instagram pre-pandemic when we bonded over a mutual love of food and old houses, cooks not infrequently in the large (Rumford!) fireplace at her home in the Catskills. “Cooking over an open flame is a great skill to develop—rather than being at the stove all night, you’re getting to hang out next to the fire with everyone else!”

If you’re curious about fireplace cooking, no special equipment is needed to get started, and one of the best places to start is with vegetables that you’d otherwise roast in the oven. “I’ll take an eggplant, wrap it in foil, and tuck it into the coals to slowly cook over an hour,” she explained, “You could also do this with potatoes or peppers or even carrots, and they get this really amazing smoky flavor.”

Want to trick your fireplace out a bit? Reach for a Tuscan grill, which Alexis explained pushes right into the fire and can be adjusted to achieve the level of heat you’re after, similar to the use of a charcoal grill. Tending to the fire is key, and you need to pay attention to what level of heat you’re after: Cooler coals are good for slower, more gentle roasting, while building up the fire is best for searing.

“We love grilling a steak! Maybe I'm also grilling scallions or red peppers to make into a romesco sauce,” There is a great romesco sauce recipe in Alexis’s cookbook To The Last Bite that John and I have made many, many times! “It doesn't have to be fussy, but if you're using really good ingredients and letting the fire work its magic, you’re bound to have an amazing meal.”

Next weekend, we’re returning to Wynkoop House, and I remember seeing a Tuscan grill amongst the various tools in the hearth. Thanks to Alexis’s advice—which you can get regularly in her substack, Side Dish—I’m inspired, and I think it’s time to give it another go. I’ll report back!

Zografos, Stamatis. Architecture and Fire: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Conservation. UCL Press, 2019, pp. 91–93. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvb6v6jq.10.

Edgerton, Samuel Y. "Heat and Style: Eighteenth-Century House Warming by Stoves." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 20, no. 1, Mar. 1961, pp. 21–22. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/988150.

Edgerton, Samuel Y. "Heat and Style: Eighteenth-Century House Warming by Stoves." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 20, no. 1, Mar. 1961, pp. 21–22. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/988150.

Brown, Sanborn C. "Count Rumford: A Bicentennial Review." American Scientist, vol. 42, no. 1, Jan. 1954, p. 124. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27826527.

I don’t think I’ve used a footnote since writing my senior art history thesis at Williams. Hello, Prof McGowan! I digress. Beehive ovens truly deserve their own post, but they are essentially brick hemispherical ovens often to the right of the firebox that adjoin with the main flue. The name comes from the conical shape, and they function similarly to a woodburning pizza oven. Claire Saffitz had a great video showing how to cook in one.

In the late 1970's, the price of beef was really high. For awhile my mom fed us nothing but chicken and hamburger. Around 1981 or 82, we could afford to steak. My dad bought this grill attached to a small pipe that allowed us to grill steaks in our fireplace in our family room fireplace. The pipe fitted vertically in the firebox and the grill swiveled in over the fire at a 45 degree angle. You had to have a mature fire that was evenly distributed with hot coals. It made for really tasty meals. But be prepared for random grease splatters. For a while, I think we had steak three times a week.

Loved being a part of this newsletter and so appreciate your thoroughness with, well, everything!